Sutton Veny, Wiltshire. 1794

It is documented in Wiltshire County History in 1794;

' The inhabitants of Sutton Veny were posted a local to attend the preaching of the gospel in Common Close Meeting. A house was licensed for the purpose of preaching the Word. Strong supporters of this church were the Imber family. Edward gave land for a chapel, three of the family were in the the first trust deed, and William led the church as first deacon until 1829 '

In the 1790's England was in a serious recession and farmers all over the country were having to lay off workers. With an unprecedented rise in the price of food and other essentials it produced a 3 and 4 times rise in poor relief. In a climate of decaying living and working standards many people were losing their dignity and hope. In large towns and cities demonstrations had turned to riot and in others civil order and moral standards were collapsing. The first police force was still 30 years away from its beginnings in London and a further 20 years for the rest of the country.

Respectable Englishmen seeing this had convinced themselves that the problem was not poverty but the lack of fundamental guidance. What followed was an outcry by writers and journalists attacking the excesses they saw in the society around them. Others sort reformation through education (particularly through Sunday Schools which would not interfere with the productivity of the other six days) and some through a wider preaching of the gospel, some through legislation and government intervention. New armies of social reformers continued to devise ways in which the poor might live more thriftily more happily and more profitably.

The village of Sutton Veny was experiencing its share of poverty. With it being located on the crossroad route to and from Salisbury, and thereby exposed to the mood of the people from the larger towns it would be easy to see how it might be influenced like so many other places into a less than sober decline.

William Imber as one can imagine would have needed considerable energy to pursue their conversion in such times and it might be guessed that as he was to serve there for another 35 years he would have been a man in his early 30's when he first became deacon.

William Imber's chapel has now gone, however the site of it can be found near the crossroads of the village where set back off the road is an old school house now converted to a private residence (left). The chapel stood in front of the school house.

This school house, probably built just after the chapel has a narrow path along the side. Where the path turns at the rear of the school house there is a small walled off area where the chapels graveyard can still be found. With overgrown and unattended graves it is evident that the descendents of the people buried there left the village many years ago (right).

Though the weathered stones make identification almost impossible there doesn't appear a memorial or headstone to William Imber. It does seem likely however, that William Imber would have been school master as well as deacon at Sutton Veny which would have been common to the part the Independant Baptists would play in education both literate and spiritual in those disturbed times.

Sutton Veny.1996

Today Sutton Veny is a quiet residential village. The large Anglican church stands 600 yards from the crossroads on the road to Salisbury.

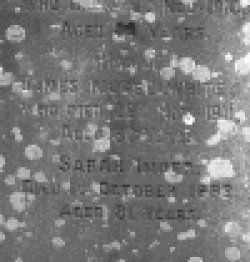

On the right hand side of the path to the church's main entrance there is the grave stone of James and Charles Musselwhite which includes the name of a Sarah Imber.(above)

Died 1882. Aged 81. It appears that Sarah had been moved to be included on the headstone of the Musselwhites as both members of that family had died in 1910 and 1911.

The 1881 census gives Sarah Imber living with James (Musselwhite) and Charlotte Imber at Sutton Veny, but unfortunately gives no relationship. Although there is a marriage certficate for a Charlotte Imber b. 20.3.1831 married on 13.7.1861 in Sutton Veny to James Musselwhite.

Sarah Imber being Charlotte's mother.

(*Charlotte is the daughter of a William Imber a farmer born 1785 in Sutton Veny.

William is shown as a pauper in 1851 and was buried on 12.10.1853 SV.

William was married to Sarah b. 1801 Heytesbury and d. 1.10.1882 SV.

She was a sempstress in 1861 and living at Deverill Rd, SV.

William and Sara's first child was Anne b. 14.12.1827 and also have 14.12.1828.

Charlotte as mentioned then Thomas b. 23.4.1834 SV and buried 1.5.1834 SV.

Another Thomas b. 1.5.1842 SV and buried 4.5.1842 SV.

Sarah Ellen b. 25.10.1846 SV married John Gay on 13.6.1876 at SV.

Witnesses to the wedding of Sarah Ellen and John Gay were James Musselwhite and George Imber.

Witnesses to Charlotte and James' wedding were Lydia Snelgrove and Frank Idy.)

*above dates and names supplied by Laurel Glaeser

Donhead St Andrew. 1797

The church of St Bartholomews at Donhead St Andrew is placed in a deep hollow with the community made up of farmsteads and hamlets on the surrounding hills with Donhead St Mary merging in places.

In the 1790's the village of Donhead St Andrew would also have been suffering from the terrible recession but with 2 churches in close proximity, the other being at Donhead St Mary on the adjoining hill, the peoples moral and spiritual needs were less likely to have been neglected. Though roads and transport were much improved, the position of Donhead St Andrew tucked into the surrounding hills and with no through route would have kept the village protected from the outside influence of travellers and drifters. With the added protection or to an extent overseeing by the richer land-owners in the area, the population of 601 people in 1801 were less likely to have had further burdens to add to their poverty than those already imposed. One of which the 'Speenhamland Act' had brought about a payment of rates in aid of wages. This relieved the employing farmer from the necessity of giving a living wage to his work people and unjustly forced the small independant parishioner to help the 'big man'. As a result the labourer was forced to become a pauper even when he was in full work.

In many southern counties, particularly in Wiltshire and those parts of the rural south furthest away from the wage competition of the factories and mines the numerous farmers who employed no payed labour themselves were made to pay heavy poor rates in order to eke out the wages paid by the large employing farmers. Even in the 1820's the agricultural labour in some places had to take part of his wages in corn and beer.

The Imber family at Donhead St Andrew. 1797

A James Imber is 'known at Donhead St Andrew' in 1797 and although up to the present no record has been found of James Imber's marriage to Elizabeth Barrett, it is here their first child, Thomas, is born.

Donhead was the home of Elizabeth Barrett who was born and presumably brought up there. She had come from a family that by trade were stonemasons which would have kept their living standards higher than the agricultural workers in the present recession.

Every landowner in the country seemed to be investing in canals, either for the profits they made or in order to open up new markets for the produce of his estate. All these activities demanded casual unskilled labour as well as stonemasons and bricklayers. With the large houses and estates in the region there would have also been the opportunity for those with the skills to be employed by this gentry. It was not unusual for these large houses to have extensions and alterations made to the original building for then the owner to have them changed again a year or two later when a new trend developed. In 1811 the nearby Ferne House was pulled down and entirely rebuilt which the Barrett stonemasons would most likely have been involved with.

1797-1817

If James was not to be employed by the Barretts and there is no record of what his employment was at the time, it would not have been unusual for him and Elizabeth to be advantaged in some way by the Barrett family. Elizabeth was to always keep her family name and it would even be continued by their daughter Marriah and later adopted by her grandson as Richard 'Barrett' Imber so it might be guessed that their influence would have been significant.

1799

2 years after Thomas was born, James and Elizabeth had their first daughter Marriah and one year later they baptised and buried their second son who was named after father James. It is interesting that there is no record of Thomas being baptised, but following children were. Were James and Elizabeth married in those two years or had the recent religious enthusiasm been the reason ? Maybe the registration of their marriage is not with the St Bartholomews. Unless of course they were never married, which was not entirely uncommon.

1804 - 1817

3 years after losing their second son at birth (baptised as James), James and Elizabeth had another boy who was also baptised as James. One year later another boy John, and 3 years after that a second daughter Mary Ann . Then a period of 9 years and their 6th and final child Caroline Frances.It was 1817, James was a labourer now aged 43 and Elizabeth was 44 and obviously a remarkably healthy woman. If there were few advantages for people in a still continuing slump it was that medicine and doctors were much improved and life expectancy had increased. The population had leapt up throughout the country and in Donhead it had increased by 50% in 10 years though this would hardly be a solution to the continuing problem of poverty.

1804 - 1817

When Waterloo was fought rural England was still in its unspoilt beauty, and most English towns were either handsome or picturesque.

The course of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) with blockade and counter blockade made business a gamble.The unnecessary War with the United States (1812-1815) was another elemant of disturbance to trade. The sufferings of the English working class were increased by these violent fluctuations of demand and employment; and unemployment was worst of all during the post war slump after Waterloo. The poor both in town and country suffered terribly from the price of bread, though it put money into the pockets of tenant farmers, freehold yeomen, and receivers of tithe and rent. During the twenty years of war the extent and character of land cultivation was adapted to these high prices, so that when corn fell at the return of peace many farmers were ruined and rents could not be paid. In these circumstances the Corn Law was passed with the aim of restoring agricultural prosperity at the expense of the consumer. The continual rise in population made it impossible to provide work for everyone and agriculture had absorbed all the hands it required. Many traditional kinds of rural occupation were disappearing. The village was ceasing to manufacture goods for the general market and moreover, was manufacturing fewer goods for itself. The cottager learnt to buy in the town many articles that used to be made in the village or on the estate. A village shop was now often set up stocked with goods from the cities or from overseas.

In 1817 James and Elizabeth's first son, Thomas, had before the age of twenty been employed as a carrier - "one who undertakes for hire the conveyance of goods and parcels" usually on fixed routes at fixed times - to bring the goods to and from the area. It appears a job more likely to be done by young men. The journeys with horse and cart in all conditions would have been hardwork. Even with the added risk of robbery in some counties.

1819 - 1829

In 1819 Thomas was married at Ansty to a local girl, Martha Turner. Ansty is just 3 miles away from Donhead St Andrew. Their first child was baptised and buried in 1823 and was named after her mother Martha.

However by 1823 Thomas had changed his job because now he is stated as being 'Yeoman' - a commoner of respectable standing and one who cultivates his own land .

A great deal of difference between being a carrier and yeoman might suggest that Thomas had inherited this land. Though this may not have been the windfall that it appears as more and more the dispossession of the independent small holder and yeoman farmers continued. The Corn Law had led to disastrous fluctuations in prices when the harvest was bad. For Thomas his new found independence could only be a continual struggle.

In 1828 a new Corn Law had been introduced to try and create more stability in the land but had turned to disaster when it produced another slump in prices. This was to be the end for Thomas as a yeoman. In 1829 he and Martha now with a young son of four years old had left the rural village and his land to move like so many others for a living in the town. In their case it was to Gillingham some 7 miles west of Donhead. His land probably now dormant or at best being worked by another member of the family.

It was in Gillingham that their second son Richard was born and here that same year a tragedy struck the young family. Thomas died. It is not recorded how. Thomas was brought back home to the village and buried at St. Bartholomews. He was just 32 years old.

Martha and her two sons immediately returned to the family in Donhead.

1829 - 1832

Thomas' land would now appear to have passed on to James (his father) who now after years of being a labourer becomes a yeoman. But at the age of 55 it might be guessed that working this land for barely a living would be as impossible for James as it was for his son. Now James either passed the land on or sold it and became a butler.

Doubtless it would not have been easy to move from being a labourer to a butler and maybe James had already been working for them as a long serving employee now promoted. It is difficult to see how James who for more than 20 years had worked as a labourer would have adapted to the requirements of butling without the benevolence of someone local who could afford to take him on in such a position. However his new found employment would last for less than 5 years.

It was also during 1829 that William Imber the deacon at Sutton Veny for the past 35 years had now either retired or died.

1832

James and Elizabeth's second daughter Mary Anne married at the age of 24 in Pitminster near Taunton (Dorset) to 36 year old butcher William Woodrow. They were to have 8 children.

The third and youngest son of James and Elizabeth was married in Taunton two years later. John was 29 years old and Sarah Cox was 26 and now living in Corfe (a village near Taunton 50 miles west of Donhead and not to be confused with Corfe Castle) they were in the neighbouring village to Pitminster where Mary Anne lived.

1834

Both John and Mary Anne had left the uncertainty of earning a living in Donhead to have a better chance in the villages just outside Taunton. While Mary Anne had married William Woodrow and was setting up house nearby as a butchers wife, John was employed as a servant just like so many others from the rural villages in the south that were forced to find an alternative to farming.

In that same year of 1834 James Imber died at the age of 60 and was buried at St Bartholomews in Donhead St Andrew. James had lived in three eras of monarchs, George III, George IV and William IV. It was just 3 years from the reign of Queen Victoria and England now without the threat of war had begun an era of dramatic change to urban and country life that was to last for the next 70 years. This period was marked by interest in religious questions and was deeply influenced by seriousness of thought and self discipline of character. It was in complete contrast to the society of 1897 when James had first arrived in Donhead.

Elizabeth, now his widow was 61 years of age. Marriah the eldest daughter was 32, James, 30, (now the eldest son as Thomas had died 5 years ago) John, 29, Mary Ann, 26, and Caroline Frances their youngest daughter, 17. It can be assumed that Marriah, James and Caroline were still living at home at the time.

1842 Another mention in the family tree of employment in 'service' was Thomas and Martha's son William who with brother Richard and mother Martha had moved back to Donhead after Thomas had died in Gillingham. William aged 17, it is recorded, was a servant at Ferne House. Which is about 2 miles south east of Donhead St Andrew and today known simply as ' Ferne '. A large house and grounds that in 1842 would have maintained a substantial staff. Maybe this is where future recordings of the family ' in service ' were employed.

1851

William now 26, had ceased employment at Ferne House probably by the time he was in his twenty's and become a 'carrier'. A carrier, being in charge of his own pony and cart, obviously had far more attractions to a young man with the opportunity to travel to village and town. William was ready to take up what his father Thomas had done at a similar age rather than persue the alternative, which was either to become a labourer like his 22 year old brother Richard, or leave the area altogether.

Being unmarried still living at home in Donhead and no doubt helping support his widowed mother Martha, it is the last known recording of William on the family tree.

Elizabeth Barrett, James' widow of some 16 years and and 78 years old was now recorded as being a servant!

That same year Caroline, 34, her youngest daughter and also a servant who had been living at home with her mother, married a bricktile maker called Job Snelgrove from Upton Lovell (about 9 miles north of Donhead St Andrew). Job, a wealthier man, also farmed 60 acres of land and lived in Donhead or in a nearby farm. He also employed 16 labourers in his brick business which was a small industry in Donhead. Job obviously a shrewd business man had like the Barrett's been able to build a good living despite the disasterous financial climate of the past decades.

It's tempting to suppose that Caroline was actually working as a servant for Job before they were married or that her mother was when the 1851 census states her as a house servant at the age of 78.

There are no other Snelgrove's buried at St Bartholomews in Donhead.

1853

It seems likely judging by later recordings that Elizabeth then left the family home where she was looked after by Caroline and Job.

One of Elizabeths other daughters Mary Ann was now 43 years old, married to butcher William Woodrow and still living in Pitminster. In 1853 just 2 years later, Mary Ann had died and was buried back home in Donhead St Andrew where her name can be still seen on the the family gravestone in Donhead along with William and Mary Anne's third son James is also buried. William was to be buried in Pitminster (1869 ) age 73. (see William and Mary Annes family)

By 1854 the eldest daughter Marriah was 55 and known to have married by now to a man with the surname of ' Hine '. This was the last known entry of Marriah on the family tree.

1858

A Richard and Mary Hine was known to be living with Caroline and Elizabeth at Donhead. Richard Hine would have been 27 years old and Mary, 25. It is noted here that they are the grandchildren of William Imber.

The name 'Hine' must be assumed to come from a married daughter of William Imber. It is unlikely to have been the same man that Marriah married unless Richard and Mary Hine's mother (Williams daughter) had died at quite a young age, but it is quite possibly the same family.

It is also noted that Richard 'Hine' was witness to Elizabeths will in 1854 but oddly is called ' Hain ' in that document. Which might well be poor writing or a clerical error.

see : Elizabeth's will.

1858 - 1859

Maybe it was the land which had been left to Thomas and had passed to James her husband on the death of their son.

An even further confusion is that the 1841 census has no surname at all but the rather baffling entry of ' richard ....' no surname : (by Barratt Mill with Caroline Imber - & Elizabeth ) showing that Richard and Mary had been living there 17 years ago when they were children. Which might indicate some unfortunate circumstance had befallen their parents. Who or what Barratt Mill is remains unknown. The only entry for Mary in 1858 is that she ' will go to service ' The last known entry for Thomas and Martha's son Richard was in also 1858. At the age of 29 he was recorded as Richard ' Barrett ' Imber which now had the addition of his grandmother Elizabeth's maiden name although it is not stated at his baptism.

1859

Elizabeth Barrett wife of James died at the age of 79 and was buried in Donhead St Andrew.

The only other entry at Donhead was when Thomas' wife Martha died 5 years later age 71.

They were the last of 3 generations of the Imber family at Donhead St Andrew. Now the children of John and Sarah would continue the line and they would all be born in Corfe near Taunton.

Donhead St.Andrew. 1996

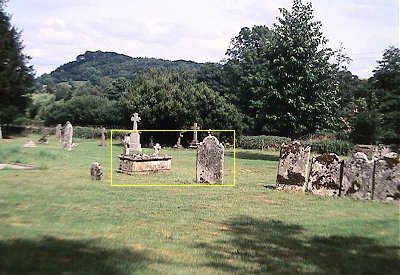

The village now quiet as a place of retirement has a population of 400 whereas in 1850 over 800. The accelerating trend for the properties to be weekend residencies means that few if any of the old families still remain. New houses have replaced many of the farm buildings. The decline to trade and business that began in the early 1800's continued into the present day where even the village shop has now gone.

Coming into the village through the winding roads and steep tree covered hills, St Bartholomews church is nearly hidden from sight nestled into the valley bottom by a narrow bridge. The picturesque view looking east from the churchyard would have remained virtually the same since James first arrived there 200 years ago.

Their gravestones can still be seen at St Bartholomews churchyard.

In the 1950's the warden listed and drew up a plan that is kept inside the church. Though the stones are much weathered and covered in lichens the names are just visible. The two stones lay only a few feet apart, (outlined yellow) the upright one numbered 99 on the church plan is the Imber family

(on the right ) the other of Caroline Frances Imber and Job Snelgrove. (on the left) -

|

(left)

(below)

|